Professor Judith M. Stinson, Executive Associate Dean of the Sandra Day O’Connor School of Law at Arizona State University and a recognized national expert on the distinctions between legal holdings and “dicta,” told The Tennessee Star that if the decision by Chancery Court Judge Claudia Bonnyman to set the date for the special mayoral election in Nashville at August 2 treated dicta as binding, that places the integrity of that election, as well as the entire judicial system in the state of Tennessee, in question.

Only a legal holding in a case on the issue argued by both sides establishes legal precedent, Stinson told The Star in a phone interview on Thursday.

“Dicta” is entirely irrelevant and is not solid grounds for a legal precedent.

Last Friday, the Davidson County Election Commission ignored the plain meaning of the law and voted 3 to 2 to set August 2 as the date for the special mayoral election.

On Wednesday, Judge Bonnyman sided with the commission and ruled that August 2 should be the date for the special mayoral election.

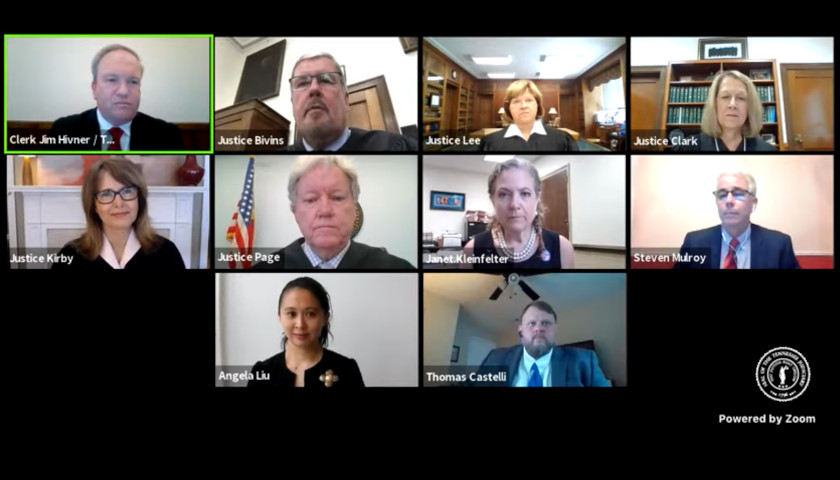

On Thursday, Jamie Hollin, attorney for plaintiff and mayoral candidate Ludye Wallace, appealed Judge Bonnyman’s ruling to the Tennessee Supreme Court, The Tennesseean reported.

Here is the key part of Judge Bonnyman’s ruling in Wallace vs. Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County, et al., as handed down on Wednesday, which relied on “dicta” from the 1983 Tennessee Supreme Court case Wise v. Judd rather than that case’s legal holdings, in the opinion of all of the more than half dozen Tennessee attorneys The Star discussed the case with:

The Tennessee Supreme Court has interpreted the phrase metropolitan general election in Metro Charter 15.01 to mean any election where Metropolitan offices are being elected. The Metropolitan Charter Section 19.01 requires that a petition for a referendum on a proposed amendment be signed by 10 percent of the number of registered voters of of Nashville-Davidson County voting in the preceding general election. And the issue in that case that the Supreme Court decided was whether the reference was to a preceding metropolitan general election, and was there such a thing, what was it; or the previous state general election which occurred in November 1982. If the August 1982 or August 1979 metropolitan election meant, facially, the petitions contained a sufficient number of signatures.

The Chancellor held that since the subject involved is the amendment of the Metropolitan Charter, the intent of the Charter Commissioners was to refer to the number of votes cast in the metropolitan election rather than to the number in a state or national election. The Charter provides for metropolitan general election and refers to them as such. We think the reference in 19.01 under consideration is to municipal elections; that is a broad meaning of the term general metropolitan elections rather than the narrow term which is touted by and argued by the plaintiffs.

The Court also finds in regard to the memorandum underlying Wise versus Judd that the August 1982 election was not the every four year general election but was the more generic broad general metropolitan election. Therefore the Supreme Court has interpreted Chapter 15.01 to mean any election where votes are cast in the metropolitan election. (emphasis added)

“A holding is generally thought of as those parts of a judicial opinion that are ‘necessary’ to the result. Dictum, on the other hand, is anything in a judicial opinion that is not the holding,” Stinson wrote in a 2010 article at the Brooklyn Law Review, “Why Dicta Becomes Holding and Why it Matters.”

“The exact result of the case combined with the relevant facts constitute a legal holding,” Stinson told The Star.

“The facts plus the outcome, that’s it. Some would include the rationale (or reasoning) as well, but not language that is extraneous to the result,” she said.

“The reason dicta isn’t binding is that the court often gives it little thought—it won’t impact the decision—and hence, it isn’t binding on other courts,” she noted.

“If it’s not the facts and outcome of the case… if what was being relied on wasn’t necessary to that decision, then the court should look at it more closely,” the Arizona State University law professor said.

“If a court relies on dicta as if it is binding (and not merely persuasive), that undermines the legitimacy of the courts,” Stinson told The Star.

“Judges aren’t supposed to legislate,” she added.

“It undermines the legitimacy of the courts. Judges aren’t bound by dicta, so they should be transparent when they are relying on dicta (and treating it as persuasive); if they treat it as binding, that effects the legitimacy of the courts,” Stinson continued.

“The court ought to look at it closely and consider what the court in Wise v. Judd did, not just what it said, to ensure the lower court didn’t give more weight to the earlier decision [Wise v. Judd] than is appropriate in this case,” she noted.

“When someone labels an earlier statement from a case as binding when it wasn’t actually the holding, it’s problematic,” Stinson concluded.

The Tennessee Supreme Court agreed with Stinson more than half a century ago, when it ruled in the 1950 case of Staten v. State, that “dictum” is not precedent:

Expediency and public policy long ago established a rule that is known to the Bar as the rule of stare decisis. This rule is that when a principle of law has been established by a court of competent jurisdiction that then in that State where such rule is established it becomes settled and binding upon the courts of that State and should be followed in similar cases.

Courts sometimes go beyond the point necessary for a decision in a lawsuit and make expressions on certain things there involved which are not necessary for a determination of the lawsuit. Such statements by a court are known as dictum. The term ‘dictum’ is an abbreviation of ‘obiter dictum’ which means generally a remark or opinion uttered by the way. Obviously the very definition of the term shows that it has no bearing on the direct route or decision of the case but is made aside or on the way and is, therefore, not a controlling statement to courts when the question rises again that has been commented on by way of dictum. Frequently and naturally dictum is persuasive, but, as a general rule it is not binding as an authority or a precedent within the rule of stare decisis. 21 C.J.S., Courts, § 190, page 309.

Thus obiter dictum is not a precedent.

You can read the opinion in Staten v. State here:

[pdf-embedder url=”https://tennesseestar.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Staten-v-State.pdf” title=”Staten v State”]

“A close look at the actual language of the Wise v. Judd decision, however, shows two things,” The Star reported last week:

- The legal point at issue was not for the court to establish what was meant by the term “general municipal election.”

- The language used by Justice Harbison in his opinion actually supports the alternative view advanced by supporters of the May 1 election date that “general metropolitan election” refers only to the quadrennial election of the mayor and members of the city council.

The West Law description of Wise v. Judd shows that, contrary to Judge Bonnyman’s statement in her ruling, the question of “was there such a thing” as a municipal general election and the additional question “what was it” were not the questions of law the Court was asked to decide in the case:

Citizens petitioned for referendum election on amendments to the charter of the metropolitan government. The petititons were challenged by local officials. The Equity Court, Davidson County, Irvin H. Kilcrease, Jr., Chancellor, held that while the number of signatures on the petitions was sufficient to satisfy charter provisions, enough signatures on the petitions were invalid as determined by reasonable procedures to disqualify them, and both parties appealed.

The Supreme Court, Harbison, J. held that (1)charter requirements that petition for referendum on proposed amendment be signed by ten percent of number of registered voters of Nashville-Davidson county voting in preceding general election referred to preceding Metropolitan general election, not previous state general election, but (2) employment of electronic data process for comparison of signatures on petition against permanent voter registration rolls which resulted in wholesale disqualifications of signatures contravened public policy of state and was therefore deemed arbitrary.

Further, the specific wording in the Wise v. Judd decision upon which Judge Bonnyman relied upon to claim “The Tennessee Supreme Court has interpreted the phrase metropolitan general election in Metro Charter 15.01 to mean any election where Metropolitan offices are being elected,” was in fact, not a legal holding, but instead “dicta.”

The Metropolitan Charter Section 19.01 requires that a petition for a referendum on a proposed amendment be signed by “ten (10) percent of the number of the registered voters of Nashville-Davidson County voting in the preceding general election.”

The issue is whether this reference is to a preceding Metropolitan general election (regularly held in August) or the previous state general election, which occurred in November, 1982. If the August 1982 or August 1979 Metropolitan elections are meant, facially the petitions contain a sufficient number of signatures. If the reference is to the state general election held in November 1982 (to which no Metropolitan offices were subject) the number is insufficient.

You can read the full Wise v. Judd decision here:

[pdf-embedder url=”https://tennesseestar.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/State-ex-rel-Wise-v-Judd-N0178530xD719A.pdf” title=”State ex rel Wise v Judd (N0178530xD719A)”]

As The Star noted, “In this decision, the Tennessee Supreme Court was asked to decided whether the “preceding general election” referred to a preceding state general election or a preceding general election that took place in metropolitan Nashville-Davidson County.”

That the purpose of the court was to choose between a preceding state election vs. a preceding municipal election, rather than to define what would be subsequently meant by the Metro Charter amendment passed more than 20 years later in 2007 by “general metropolitan election” appears to be confirmed by the specific language used by the court.

They refer to the November 1982 election–at which municipal judges and the sheriff were elected, not the mayor and city council members–as a “Metropolitan general election” and not as a “general metropolitan election.” In other words, it seems more likely that the court was describing “a general election that took place in metropolitan Nashville-Davidson County,” and not a “general metropolitan election” as referred to in Section 15.0.3 of the Metro Charter.

It is unclear whether the Tennessee Supreme Court will “reach down” to rule on the plaintiff’s appeal in Wallace vs. Metropolitan Government of Nashville and Davidson County, et al.

One thing, however, is clear as a bell.

The important issue here is not whether the special mayoral election will be held on May 1 or August 2.

At stake is public confidence in the legitimacy of the special mayoral election as well as the legitimacy of the entire judicial system and the rule of law in the state of Tennessee.

The rule of law, especially the U.S. Constitution, hasn’t been followed for years in our country so why should we think that it would be followed in the state?

The leftist narrative is that the laws have been made mostly by dead and “alive” white men so they’re bigoted and racist and we don’t need to follow them. They truly think that they are above the law, like Hillary, Obama, Holder, Comey, etc.

Wow! This is well above my understanding of jurisprudence, but it seems fitting that “dicta” is involved in the replacement process for ex-Mayor Moonbeam.

Keep the pressure on! Fair, and accurate elections are THE single most important function that a representative form of Government provides to it’s citizens!